If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, who giveth to all men liberally and upbraideth not. -James, chapter 1 verse 5

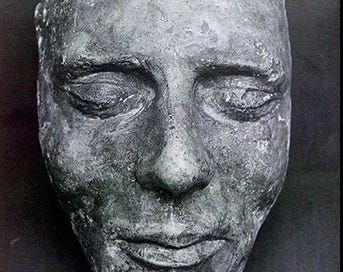

This verse inspired Joseph Smith’s 1820 prayer for wisdom. That prayer was also his baptism in the deep water of contemplative spirituality—an aquifer1 sustaining every enduring religious tradition. Joseph’s consequent ego-death, phenomenal annihilation, and sudden theophany which are self-reported in his history are gorgeously prototypic of the mystical trajectory.

In the theistic landscape, a mystic is an individual who seeks a direct experience or union with God’s own being through contemplation and self-surrender. Contemplation, in turn, is a theological term of art which refers to a profound form of prayer or meditation focused on seeking deep, direct, experiential connection with the Divine.

Contemplative prayer can be contrasted to discursive meditation, which is when the mind actively reasons about religious concepts. Although discursive meditation and active reasoning can at times be spiritually fruitful, contemplation aims to transcend ordinary thought by quieting the mental faculties and becoming ultimately receptive to the Holy Spirit—the personage of loving wisdom.

This can feel foreign in our culture of hyperactivity. Joseph Smith points to the superior value of contemplative over discursive religion, though, by declaring, “The best way to obtain truth and wisdom is not to ask from books, but to go to God in prayer, and obtain divine teaching.” Joseph additionally stated, "Could you gaze into heaven five minutes, you would know more than you would by reading all that ever was written on the subject."

Contemplative spirituality has roots that are thousands of years old. In Hebrew scripture, Solomon asked the Lord to grant him a “listening heart” (Hebrew: “lev shomea”) for the explicit purpose of obtaining wisdom. This gift of a listening heart, or “lev shomea”, is characterized by a state of pure awareness and receptivity. The Psalmist expresses it thusly: “For God alone my soul waits in silence.” Later Christian scripture reaffirms the merit of contemplative spirituality (e.g., “Be still and know that I am God.”) As we practice the spiritual art of centering our attention lovingly on God, we cooperate with grace expressing itself in a reformation of our consciousness toward a simplex of lovingwisdom. Interpretively in a Christian paradigm, this represents a growing awareness of the Holy Spirit’s ubiquitous influence.

The Doctrine & Covenants, a book of Latter-day Saint scripture, centralizes a listening heart in its dual epistemology of revelation, which spans both the discursive and the contemplative faculties: “I will tell you in your mind and in your heart, by the Holy Ghost, which shall come upon you and which shall dwell in your heart” (D&C 8:2). Joseph Smith thus encouraged the contemplative novice: “A person may profit by noticing the first intimation of the spirit of revelation.” The Doctrine & Covenants describes a fuller measure of contemplative grace in evocative language: “the still small voice, which whispereth through and pierceth all things, and often times it maketh my bones to quake while it maketh manifest” (D&C 85:6).

We often hear Joseph Smith described as a prophet, seer, and revelator, but rarely, if ever, do we hear him described as a mystic. Perhaps part of the reason for this is that the roles of prophet, seer, and revelator are outwardly facing spiritual mantles marked by the responsibilities of public leadership, whereas the role of mystic is one of an inwardly kept private relationship marked by profound and personal intimacy with God. I think, too, that the later hyper-industrialism of Brigham Young and the Mormon pioneers inadvertently decentralized and obscured the contemplative spirituality of Joseph’s legacy—a trend which persists in contemporary Latter-day Saint culture.

This dichotomy of outward facing versus inward keeping is materially presented to us in the history of the Book of Mormon itself. The Golden Plates (whether one understands them as a physical object or a symbol of the psyche) are described as being largely sealed, such that two-thirds of their content was kept private. This can be a deeply instructive metaphor of our spiritual communion: letting there be more that is unseen than seen, more that is unspoken than declared. Through the Golden Plates, the ethos of sacred silence is made present at the genesis of Latter-day Saint spirituality.

By its nature, silence often goes unnoticed. You can’t write pages of quiet. But we undervalue the Restoration’s quiet throughline of mysticism at our own peril. Yes, the promise of Christian spirituality has always been, “Ask and ye shall receive” (Matthew 7:7; Moroni 10:3-5). But the space between asking and receiving is essential. Neglecting a contemplative dimension in spiritual life can lead to a shallow understanding of faith that distorts the religion of Christ, prioritizing outward performance over personal experience. Without contemplation, the connection to the divine may become intellectual rather than experiential. We can possibly lose empathy, insight, and the ability to cope with life's complexities. It may also hinder personal growth and a deeper, more meaningful engagement with spiritual truths.

In fair warning, you will be criticized if you pursue contemplative discipleship, especially by those who have an outwardly active religious disposition. Consider the iconic examples of Mary and Martha of Bethany: both were about good things. Martha was performing physical devotions for Jesus while Mary simply sat at His feet, gazing and hearing. Martha complained against her sister for not being more active. But Jesus affirmed that it was Mary alone who accomplished “the one thing necessary” when she suspended her physical activity and listened lovingly to him (Luke 10:42).

Lastly, one of the great evidences supporting Joseph Smith’s identity as a mystic is found in the rending cry of his woundedness when God’s Spirit withdrew its presence. Joseph enjoyed a sufficiently intimate union with God, that the withdrawal of God’s Spirit agonized him. “O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?” (D&C 28). This languishing is nearly identical to the agonized cry of Saint John of the Cross, who is known in historical Christianity as “the mystical doctor.” John writes, “Where have You hidden Yourself, And abandoned me in my groaning, O my Beloved?” (Spiritual Canticle, stanza 1). We can even see this love wound in Mary Magdalene who sobbed, “they have taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laid him.” Indeed, one way to guage our growth in mystical union is by the grief we feel when, for whatever reason, we experience distance come between ourselves and our divinely Beloved.

As we reflect on the spiritual journey of Joseph Smith, the parallels between his experience and the contemplative paths described by mystics across history are striking. Smith’s journey serves as a reminder that the path to divinity is not solely found in the external world of rituals and dogmas; they are rather found in the innermost realm of our hearts. Like the wisdom of Solomon’s listening heart, Smith's teachings illuminate the importance of silent, inward surrender to experience the divine directly, even if that arc of his teaching has been obscured by the admirable yet perhaps hyper-industrial attitudes of Brigham Young and the Mormon pioneers. In the silence of contemplation, one can find a bridge between the outward and inward, the seen and unseen, the spoken and unspoken, realizing that our faith is not only an intellectual exercise, but an experiential encounter. This mystical perspective, embodied in the life of Joseph Smith, calls us to a deeper understanding of our spiritual lives, acknowledging that the divine mystery can never be fully articulated, but only intimately known.

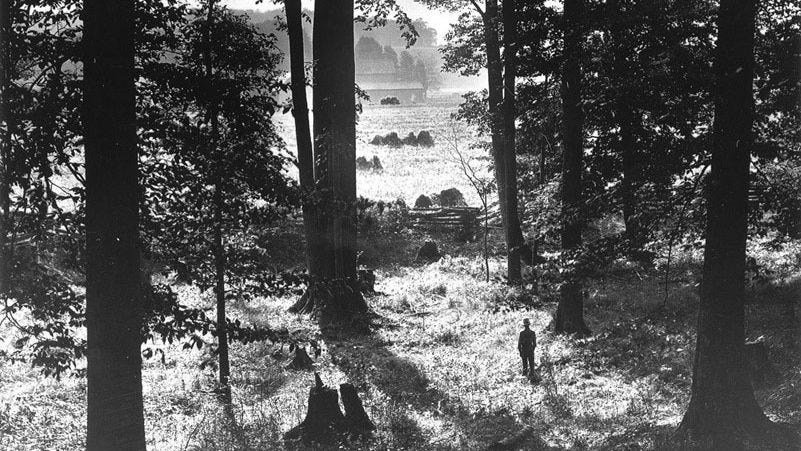

I find it provocative to consider Joseph’s youthful efforts to locate groundwater with a divining rod to be a richly symbolic foreshadowing of his eventual efforts to discover spiritual water.

That’s beautiful, Michael. I feel the spirit as I read it.

You made a good attempt to articulate the inarticulable. You might be interested in Paul Toscano's interview recently where he tries to articulate why he still thinks sacred texts like the Book of Mormon have value. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcS5MRx_t-Q